NGI The Weekly Gas Market Report | LNG | LNG Insight | Markets | NGI All News Access

LNG’s Wintry Price Plunge Boosts Possibility of U.S. Terminal Shut-Ins Later in Year

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) prices are trading near unprecedented lows, cratering at the height of winter in the northern hemisphere and again raising the possibility of shut-in exports later this year along the Gulf Coast, where supplies continue to increase.

A mild winter in North Asia and Europe, coupled with a flood of supply, as well as a mysterious coronavirus outbreak in China weighing on travel, the economy and industrial demand, continue putting pressure on prices. A similar trend has unfolded in the United States, where warmer weather has all but crushed gas prices, which fell below the $2.00 mark last week and haven’t budged.

In Europe and Asia, benchmark prices look similar to those of the United States, where they already were stifled by the Lower 48 gas boom. A steady flow of LNG supply from places like Australia, Qatar and the United States has flooded the market, with new global supplies over the last two years exceeding 53 million metric tons/year, according to Evercore ISI. In Europe, the typical pipeline flows from Algeria, Norway and Russia have also continued unchecked this winter, adding to the glut.

“I haven’t seen prices this low before,” said long-time LNG trader Brad Hitch, a former portfolio manager at Cheniere Energy Inc.

ClipperData’s Kaleem Asghar, director of LNG analytics, said he sees a “bearish trend” for prices over the next five years. There is so much global supply, he told NGI, that if one or two LNG production facilities were to go offline anywhere in the world, it would do little to move global prices.

In Asia, March gas at the Japan Korea Marker was trading at $4.00/MMBtu on Tuesday, a floor for the benchmark that hasn’t been seen since 2016. The April contract was at $3.665. The Dutch Title Transfer Facility, a primary benchmark for European LNG spot trades, was at $3.489 for March, while the National Balancing Point in the UK was at $3.662.

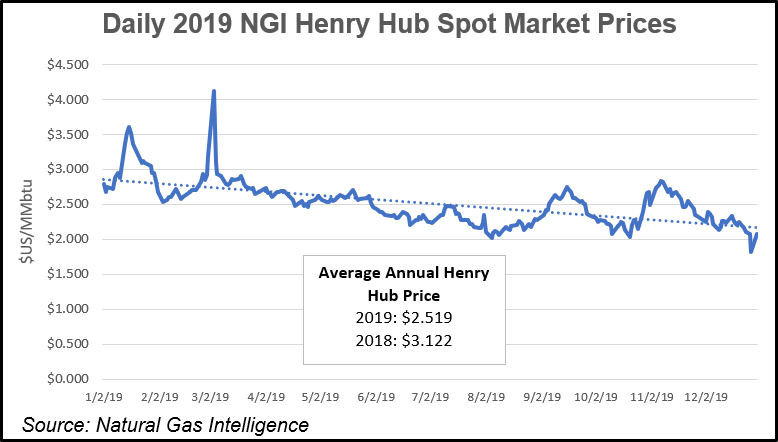

The strip for all three points is below $4.00 for most of the year. By comparison, Henry Hub prices averaged $2.519/MMBtu in 2019 and $3.122 in 2018. The New York Mercantile Exchange February contract settled at $1.934 on Tuesday, while March was at $1.908.

The arbitrage spread, or profit margin, on Monday between the Sabine Pass LNG terminal on the Gulf Coast and Asia was 13 cents/MMBtu and 34 cents to Europe, according to NGI calculations. That has moved up in recent days as vessel rates have declined on a lack of demand.

“That 34-cent spread to Europe doesn’t include regasification or pipeline access fees, and those can range between 10-50 cents on a variable basis, depending on the particular company involved,” said NGI’s Patrick Rau, director of strategy and research. “Again, nothing that screams please send as much gas from the U.S. to Europe as possible.”

Even longer-term oil-linked LNG contracts, a staple across the world, have moved little over the last year. For example, Brent crude has moved in such a narrow bandwidth that parity prices have been rangebound at about $10.00/MMBtu since last January.

As demand has weakened in Asia, Europe has come to the rescue with its ample regasification capacity, liquid trading markets and strong demand to serve as the global balancing arm. But given the supply glut and corresponding plunge in prices, concerns are increasing that some U.S. export cargoes could be canceled and shut-in.

U.S. liquefiers have more flexible contracts and a massive wholesale market to pump their volumes back into, but shut-ins and canceled cargoes aren’t likely to happen anytime soon. Even if they were, it’s unclear how long shut-ins would last as vessel rates would likely fall along with U.S. spot prices in a way that would reopen the arbitrage window and again incentivize exports.

“We’re in uncharted territory with these prices, to be honest,” Hitch told NGI on Tuesday. “And the thing we’re not going to know for a while is whether we’re in uncharted territory in terms of summer demand and summer injection capability in Europe.”

Asghar, who formerly negotiated supply agreements in Pakistan, thinks shut-ins or cargo cancellations along the Gulf Coast are unlikely given how LNG is bought and sold. Most U.S. terminals are underpinned by long-term agreements that make it difficult to cancel cargoes. However, cancellations would send a bearish signal to the market and likely push prices lower, he said.

Energy Aspects gas analyst James Waddell, who is based in London, said shut-ins aren’t likely anytime soon. He noted that U.S. offtakers have hedged their volumes against other delivery points overseas that for now would make it uneconomic to not lift a cargo.

However, contracts don’t necessarily force buyers to take cargoes in all instances or preclude parties from coming up with alternate solutions if it makes little sense to take a shipment. Instead, a variety of things, including contractual terms, vessel availability, scheduling restrictions along the Gulf Coast, and the supply and demand balance are sure to factor into the possibility of shut-ins, Hitch said.

“I think the question of whether or not there can be shut-ins is a little bit of a complicated one.”

If they do happen, shut-ins are more likely to occur later in the year, and would largely hinge on Europe’s ability to inject gas and store LNG supplies during the summer months. LNG inventories are currently at about 60% of tank capacity, or above where they typically are during winter, while the continent’s gas in underground storage is also above average at 72%.

“There are a lot of variables in play still, but the trajectory that we’re on right now, given where prices are, would tend to make me think that you’re going to have too much gas in storage in the third quarter to inject at healthy rates,” Hitch said of the European market. “If that’s the situation we’re in, that’s when the U.S. is probably at its most susceptible to shut-in.”

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 1532-1231 | ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 1532-1266 |