Shale Daily | NGI All News Access | Permian Basin

Abundant Lower 48 Natural Gas, Oil Resources Said Boon and Bane for U.S.

U.S. dry natural gas production is forecast to grow at a considerably slower rate to 2025, but it still is seen outpacing demand, pressuring prices and leading to an increase in exports, according to government projections.

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) on Wednesday issued the Annual Energy Outlook 2020 (AEO2020). The Reference case, considered EIA’s most likely scenario, shows dry gas output growing by 1.9% annually from now through 2025, “considerably slower than the 5.1%/year average growth rate from 2015 to 2020.”

The Reference case, which serves as a baseline modeled projection to explore varying assumptions about the economy, technology and policy, examines a future where slower growth in consumption in an increasingly energy efficient U.S. economy contrasts with increasing energy supply because of technological progress in renewable sources, oil and natural gas.

“We see renewables as the fastest growing source of electricity generation through 2050 as cost declines make them economically competitive beyond the expiration of existing federal and state policy supports,” said EIA Administrator Linda Capuano. “With continued technologically enabled growth in domestic oil and natural gas production, we see the United States remaining a net exporter of energy for some time.”

The percentage of dry gas production from domestic oil formations increased to 15% in 2018 from 8% in 2013, and it should remain near 15% through 2050, according to the Reference case.

“Increased drilling in the Southwest, particularly in the Wolfcamp formation in the Permian Basin, is the main driver of growth in natural gas production from tight oil formations.”

The AEO2020’s Low Oil Price case, reflecting a West Texas Intermediate average at $56/bbl or lower, “is the only case in which U.S. natural gas production from oil formations is lower in 2050 than current levels.”

Drilling in oil formations primarily is based on crude prices rather than gas prices, EIA noted. “Increased natural gas production from oil-directed drilling puts downward pressure on natural gas prices throughout the projection period.”

Henry Hub prices in the Reference case “remain lower than $4/MMBtu throughout the projection period.”

Growing demand in domestic and export markets “leads to increasing natural gas spot prices at the U.S. benchmark Henry Hub through 2050 despite continued technological advances that support increased production.”

U.S. gas prices are forecast to remain under the $4 handle through 2050 “because of an abundance of lower cost resources, primarily in tight oil plays in the Permian Basin. These lower cost resources allow higher production levels at lower prices during the projection period.”

To quench the growing overseas demand for U.S. gas, producers also are expected to expand “into less prolific and more expensive-to-produce areas, putting upward pressure on production costs.”

Domestic gas consumption in the Reference case is seen slowing after this year and remaining relatively flat through 2030 because of declining industrial sector growth. Demand also is forecast to ease in the electric power sector.

“After 2030, consumption growth rises almost 1%/year on average as natural gas use in the electric power and industrial sectors increases,” the AEO2020 said.

U.S. gas output is forecast to grow at a faster rate than consumption in most of the Reference models after 2020, which could result in more overseas exports. The only exception is the Low Oil and Gas Supply scenario, where output and consumption remain relatively flat because of higher production costs.

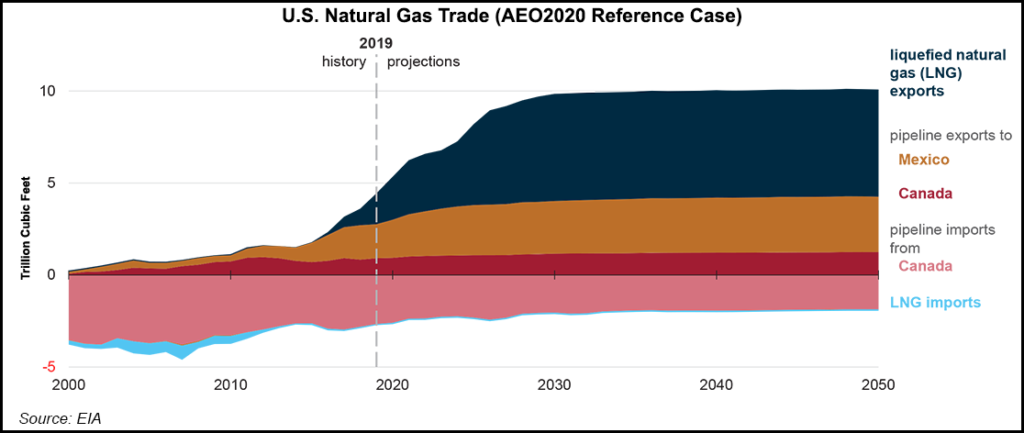

The United States is seen exporting more gas than it imports in the most likely scenario because of near-term growth in liquefied natural gas (LNG) export capacity.

“In the AEO2020 Reference case, pipeline exports to Mexico and LNG exports to world markets increase moderately until 2025, after which pipeline export growth to Mexico slows,” researchers said. “LNG exports continue to rise through 2030 before remaining relatively flat for the remainder of the projection period.”

Increasing gas exports to Mexico should follow from more pipeline infrastructure to and within the country, allowing for increased gas-fired power generation. However, by 2030, “Mexico’s domestic natural gas production begins to displace U.S. exports.”

Domestic LNG export capacity should continue to serve growing global demand, particularly in emerging Asian markets “as long as U.S. natural gas prices remain competitive,” researchers said. “As U.S.-sourced LNG becomes less competitive in world markets after 2030, export volumes level off.”

Most LNG historically has been traded under long-term contracts linked to crude prices because the regional nature of gas markets prevented a gas price index to be developed that could be used globally, EIA researchers noted.

“As more natural gas is traded via short-term contracts or traded on the spot market, the link between LNG and oil prices weakens over time, making U.S. LNG exports less sensitive to the crude oil-to-natural gas price ratio and more responsive to the global LNG supply-natural gas demand dynamics.

“This shift causes growth in U.S. LNG exports to slow in all cases.”

Under the Reference case, domestic gas output is expected to climb because of continued development in tight and shale resources, which should account for 90% of dry gas production by 2050.

“This growth is a result of the size of the associated resources, which extend over nearly 500,000 square miles, and improvements in technology that allow development of these resources at lower costs,” researchers said.

In the High Oil and Gas Supply case, which has more optimistic assumptions regarding resource size and recovery rates, cumulative production from shale/tight gas and tight oil is 14% higher than in the Reference case. Conversely, in the Low Oil and Gas Supply case, cumulative production is 20% lower than in the Reference case.

“Across all AEO2020 cases, onshore production of natural gas from sources other than tight oil and shale gas, such as coalbed methane, generally continues to decline through 2050 because of unfavorable economic conditions for producing these resources,” researchers said.

“Offshore natural gas production in the United States remains relatively flat during the projection period in all cases, driven by production from new discoveries that generally offsets declines in legacy fields.”

Broken down by area in the Lower 48, the Reference case sees “eastern” U.S. gas production, which would be centered in Appalachia, to lead shale gas growth, followed by gains in the Gulf Coast onshore area.

“Total U.S. natural gas production across most AEO2020 cases is driven by the continued development of the Marcellus and Utica shale plays in the East,” EIA said. “Natural gas from the Eagle Ford (co-produced with oil) and the Haynesville plays in the Gulf Coast region also materially contributes to domestic dry natural gas production.”

Associated gas production from tight oil resources from the Permian “greatly increases until 2022 but remains relatively flat afterwards to 2050.”

The Reference scenario shows, as expected, that technological advancements and improvements in industry practices will lower production costs and increase oil and gas volume recovery per well.

“These advancements have a significant cumulative effect in plays that extend over wide areas and that have large undeveloped resources (for example, Marcellus, Utica, and Haynesville),” EIA noted. “Natural gas production from regions with shale and tight resources shows higher levels of variability across the AEO2020 supply side cases compared with the Reference case because assumptions in those cases target those resources.”

Meanwhile, through 2050, only the industrial sector shows markedly increased gas consumption, the Reference case showed.

“The industrial sector, which includes fuel used for liquefaction at export facilities and in lease and plant operations, consumes more natural gas than any other sector in the United States after 2021.”

Gas used for U.S. electric power generation is seen peaking in 2021 as relatively low prices, new gas-fired combined-cycle capacity and coal-fired capacity retirements drive increases in gas-fired generation in the short term.

“However, strong growth in renewables and efficiency improvements in the remaining coal-fired fleet lead to declining amounts of natural gas consumed in the electric power sector through 2030,” researchers said. “Natural gas consumption then slowly rises to reach its 2021 level again in the late 2040s.”

Gas consumption in the residential and commercial sectors remains largely flat in the most likely scenario “because of efficiency gains and population shifts to warmer regions that counterbalance population growth.”

Gas demand is expected to increase in the transportation sector, particularly for freight trucks, rail and marine shipping, but “it remains a small share of both transportation fuel demand and total natural gas consumption.”

Once a reliable trading partner for gas, Canada’s imports, primarily from its prolific Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, are expected to continue to “generally decline from historical levels.” Domestic exports to Eastern Canada, however, should increase because of the region’s proximity to Appalachian resources and because of new pipeline infrastructure.

“However, this export growth slows in the mid-2020s as Canada’s demand for natural gas begins to decline, particularly in the electric power sector, as Canada begins transitioning to more renewables in its generation mix.”

EIA also provided forecasts for energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, which it said should fall until around 2030 then resume growth, “but by 2050 are lower than 2019 levels.

“For the next decade, U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions decrease because of retirements of coal-fired generation capacity and corresponding changes in the fuel mix for electric power. Later, increases in energy demand due to growth in transportation and industry cause emissions to increase.”

In addition to the AEO2020 baseline Reference case, EIA used eight side cases to explore uncertainties. New in the AEO2020 are two cases that explore the implications of varying the assumed future costs of renewable power generation technologies.

© 2024 Natural Gas Intelligence. All rights reserved.

ISSN © 2577-9877 | ISSN © 2158-8023 |